Beyond imaging the “invisible,” the x-ray image inaugurated an overt interest in scientific photography for many artists. Per Linda Dalrymple Henderson, Wilhelm Röntgen’s discovery of x-rays in late 1895 “triggered the most immediate and widespread reaction to any scientific discovery” until the atomic bomb of 1945.[1] While Dalrymple Henderson argues in “X-Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists” that the x-ray phenomenon as circulated through public, spiritualist, and artistic imaginations ultimately provided an entryway into creative explorations and meditations on the fourth dimension as seen in the work of the Cubists and Marcel Duchamp, little attention has been paid to the broader impact of x-ray imaging on the European avant-garde.

In the oeuvre of László Moholy-Nagy, x-rays and affiliated scientific photography have an even more prominent role. As Herbert Molderings writes,

an analysis of Moholy-Nagy’s theory of photography…clearly shows that modern photography evolved from a fusion of the aesthetic of scientific photography, the playful practices of amateur pastime photography and a basically Constructivist understanding of material and technique.

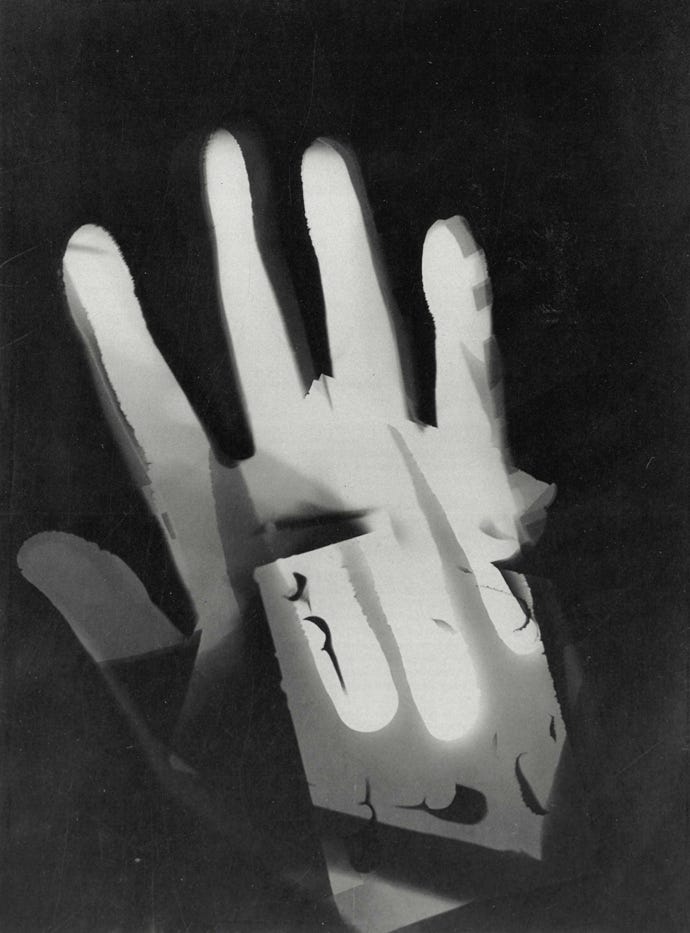

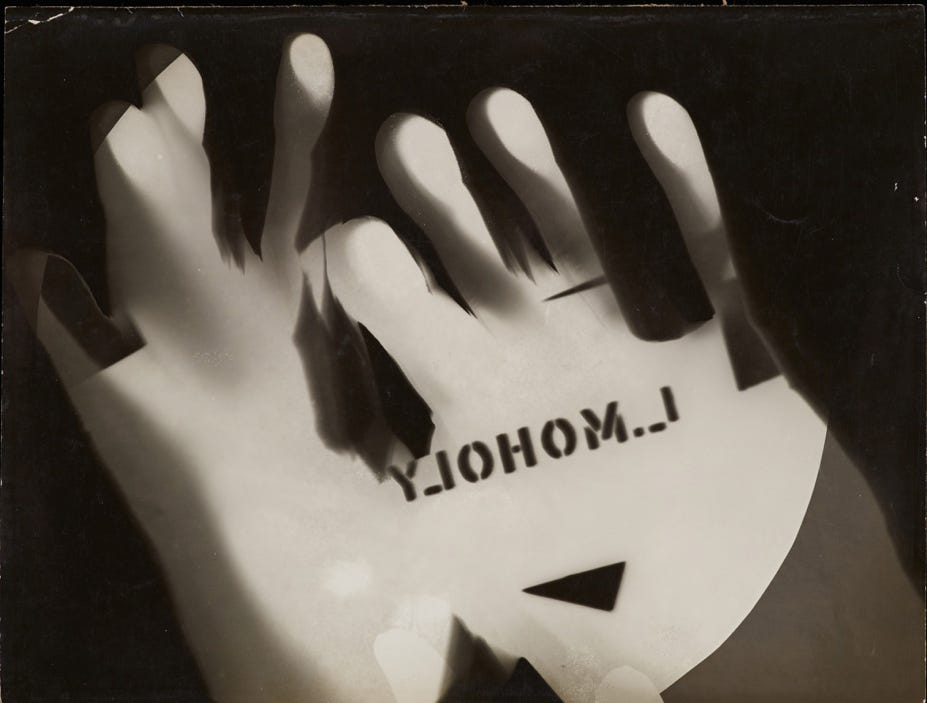

Central to this “fusion” is the x-ray image—what Moholy-Nagy himself described as the only non-reproductive photographic technique developed since the rise of photography as a medium. I trace here the conceptual tensions between the aesthetic and the scientific represented by Moholy-Nagy’s interest in x-rays: first, I outline their place within his photographic theory before I posit that Moholy-Nagy’s hand photograms from 1925-1926 specifically reference his own x-ray experiments as well as an ongoing fascination with the x-ray image’s formal qualities. Based on dating the works and formally analyzing them, I argue that Moholy-Nagy repeatedly subjected himself to “the greatest experience” of “the body being penetrated by light” in the form of “x-raying” his hand to create the hand photograms.[2]

As represented by the avant-garde photobooks like Moholy-Nagy’s Malerei, Photographie, Film (1925/27) and Franz Roh and Jan Tschichold’s Foto-Auge (1927), members of the Neues Sehen photographic movement were fascinated by x-rays even thirty years after their discovery. The “new vision” in Weimar photography constituted an effort to engage with that which exists beyond normative human perception and to communicate that in a more “objective” fashion. No longer merely reproductive, photography itself became generative and instructive. Simultaneously invested in the history of photographic practice and modernist organizations of perceptual experience, artists like Moholy-Nagy and Roh embraced the “new vision” of photography as a means with which to hone visual perception to transcend the limits of human cognition. Such a “new vision” attempted to communicate by defamiliarizing, teaching something about the world and our engagement with it precisely by abstracting it into something differently tangible and legible. That x-rays and other “applied” images were recuperated by Neues Sehen practitioners suggests not only a fundamental interest in what is made visible through scientific apparatuses but also a belief in the possibility of “objective” abstraction that was still used for expressive, artistic purposes.

Malerei, Photographie, Film is accepted as Moholy-Nagy’s major treatise and “the program for his New Vision.”[3] In the 1925 essay, he lays out a conception of art that embraces the creative possibilities of photography—of “chiaroscuro in place of pigment,” of tension between black and white as essential to the operations of light and integral to combatting the “grey” blur of modernity.[4] Therein, he defines photography as the pursuit of “objective representation” through mechanical—decidedly not “manual” means.[5] He assigns photography to the realm of tone (light) and painting to the realm of color, ascribing each a specific relationship to composition. Moholy-Nagy eschews representational compositions and “imitatively derived” elements, instead arguing that photography is better suited for the production of relationships of gradient and form: “people have discovered on the one hand the possibility of representing, in an objective, mechanical manner, the effortless crystallising out of a law stated in its own medium; on the other hand it has become clear that color composition carries its ‘subject’ within itself, in its color” [emphasis is Moholy-Nagy’s]. Concerning himself then with the productive rather than reproductive task of the new photography, he writes: “Every innovation since introduced - with the exception of X-ray photography - has been based on the artistic, reproductive concept prevailing in Daguerre's day (c.1830): reproduction (copy) of nature in conformity with the rules of perspective.”[6] What set apart the x-ray was not only its cameraless, direct positive nature but also that it was productive insofar as it displayed elements and forms of the body invisible to the naked eye.

In articulating the stakes of his art, Moholy-Nagy posits binaries he neither reconciles nor attempts to. While praising “mechanical” photography, he suggests essential and biological operations of color and form. There is expressed tension between the ability of the eye to be trained—connoisseurship of a sort—and praise for the trailblazing efforts of amateur photography (it is significant that in the years following its discovery, x-ray photography blossomed into a robust amateur tradition, with exhibitions populated by professional radiologists and amateurs alike)[7]. There is celebration of the liberation of photography from the limitations of human perception and pictorialist, re-presentative aesthetics, but there is also discussion of the camera as prosthetic, an intervention into the bodily schema through which photography itself becomes deeply embodied. As art historian Pepper Stetler writes of Malerei, Photographie, Film’s essential tension:

The book’s unwieldy photographic collection oscillates between objective record and visual spectacle, yet these two polar categorizations reinforce each other. The photographs appear all the more wondrous because of their visual “truth,” and the status of the photographs as spectacle is upheld by their foreignness to our own sense of sight. The photographs exemplify the double duty of the medium, capable of producing an objective, scientific truth while also providing a form of entertainment.[8]

These tensions emerge as tones and gradients, blacks and whites that interplay and inform rather than negate the other much as in Moholy-Nagy’s photograms themselves. It is perhaps not the dissolution of binaries that Moholy-Nagy intends, but a parallel interrogation of binaries that investigates the way they inform each other. In turn, Moholy-Nagy gives equal space to his written treatise and the curated photographs reproduced to accompany it. He uses images to re-iterate his textual argument and vice versa; his use of scientific images is at once earnest and rhetorical: “By including images of scientific study, Moholy-Nagy associates his theory of photographic perception with scientific objectivity and technological advancement.”[9]

Per Oliver I. A. Botar, these expressed tensions in Moholy-Nagy’s work are reflective of an exhibition climate in which both art and applied photography were shown side by side. The adoption of scientific photography by Neues Sehen avant-garde subsequently had a dual effect:

Moholy-Nagy’s project could be seen to be a kind of ‘scientization’ of aesthetic vision. But because Moholy-Nagy was emerging during the 1920s as a real force within the German avant-garde art scene, his suggestion had the reverse effect as well, one which re-focused aesthetic attention on scientific images.[10]

Botar also discusses at length the impact of Raoul Francé on Moholy-Nagy, who would go on to cite heavily from Francé and champion Francé’s Grundformen [basic forms] that constitute all living things.[11] Botar argues that Moholy-Nagy’s aesthetic philosophy is thus inherently biocentric if not also Monist, subsequently concluding that Moholy-Nagy’s spiral photogram was included in the book to directly reference the importance of spirals in nature (seen directly proceeding the x-rayed nautilus shell) [12].

Of additional x-ray images in Malerei, Photographie, Film, Botar writes,

In the spread of two x-ray images, one of human hands and the other of a frog, we are not only experiencing “the penetration of the body with light [as] one of the greatest visual experiences,” as Moholy-Nagy’s caption puts it, he is also demonstrating the parallels between our own skeletal structures and those of animals and he is pointing out our status as just one of the many zoological species.”[13]

But Moholy-Nagy also expresses profound appreciation for x-ray photography independent of biological subjects: in 1927 he lists x-ray photography (also described as “experiences in photography with regard to lack of [naturalistic] perspective and penetrability”) as a way to produce “unknown forms of representation” [unbekannte Formen der Darstellung] before describing the similar utility of photograms as aesthetic exercises.[14] On the following page, he elaborates: “Today it’s easy to predict that our eyes…will have rich pleasures and stimuli from similar works in the near future. The same applies to the use of Röntgen photographs.”[15] He then defines the x-ray image as a photogram itself: “A Röntgen photograph is also a photogram, an image (in this case of an object) taken without a camera. It permits us to look inside the object and reveals its outer form such as its construction through a simultaneous penetration.”[16] Moholy-Nagy supplies his readers with a figure (notably dated 1925) more mechanistic than biocentric: a simple pen. Later, Moholy-Nagy would advocate for the aesthetic grounds of x-rays in the 1929 Film und Foto Deutsches Werkbund exhibitions in Stuttgart and Berlin by curating entire sections of (human) x-ray transparencies and by prominently featuring his own Huhn bleibt Huhn (1925), a photomontage incorporating a found x-ray image into an undeniable “artwork” that features the ovular forms that reappear in some of Moholy-Nagy’s photograms of the period.[17]

Having heretofore established the profound impact that x-ray imaging and scientific photography more broadly had on Moholy-Nagy, I hope to approach his photograms as artistic analogs to x-ray images. As Neues Sehen practitioner and art historian Franz Roh wrote in his introduction to the 1930 60 Photos collection of Moholy-Nagy’s work, “Moholy-Nagy and the New Photography,” “the photogram is as old as the photograph.”[18] Photograms were purportedly first created by William Henry Talbot, who called them “photogenic drawings” and discovered the technique by applying objects to sensitized paper.[19] While the direct positive imaging process was not new, it was revived in the interwar period by members of the international avant-garde. It is widely debated, however, who invented the photogram: per Louis Kaplan, “There are at least four pretenders to the photogrammical throne—El Lissitzky, Man Ray, Christian Schade [sic], and Moholy.”[20] Moholy-Nagy defined photograms as “cameraless photographs [made] through direct exposure of the photographic medium” [kameralose Aufnahmen durch direkte Belichtung der photographischen Schicht] [21] and supposedly independently discovered them in 1922 alongside Man Ray in Paris, though both follow Christian Schad’s development of the genre with his 1918-1919 schadographs.

Schadographs represent the earliest abstract photograms made purely for an artistic purpose and, like the later “rayographs,” depend on both the naming convention and the spectacularity of Röntgen’s early x-rays known as “röntgenograms.”[22] When compared to Schad’s abstract, collage-like photograms, Man Ray’s “rayographs” of the period are more representational. In contrast to Man Ray, however, Moholy-Nagy’s photograms are more formally experimental, and echoing his paintings of the period and anticipating some of the geometric motifs seen in his later Light-Space Modulators. While Moholy-Nagy continued to make photograms into the early 1940s, his photograms from the 1920s are distinct investigations into the photogram’s capacity to express gradient and non-reproductive images. These early photograms, phantastic and “pure” [rein], adhere to the basic formal schema of many early x-ray images: as in all forms of photography--scientific or otherwise--x-ray images also come with conventions, like their planar organization of space that flattens the materiality and dimensionality of its object into tones of gray against the dark relief of indeterminate depth. Moholy-Nagy’s hand photograms from 1925-1926 are then not formal experiments so much as they are Moholy-Nagy’s contribution to a genre of photographs considered experimental and necessary to documenting a revolutionary phenomenon.

The distribution of photograms and x-rays in Malerei, Photographie, Film demonstrates Moholy-Nagy’s guiding photographic principle that “organised effects of light and shade bring a new enrichment of our vision.”[23] Four x-rays in Malerei, Photographie, Film are interspersed with photograms from Moholy-Nagy as well as Man Ray, with Moholy-Nagy captioning an x-ray of a frog, “Penetration of the body with light is one of the greatest visual experiences.”[24] Moholy-Nagy then subjects himself repeatedly to this experience by repeatedly photogramming his own hand. Not only is the photogrammic process—the exposure of photosensitive paper with objects on its surface—most similar to the x-ray’s plate-based process (exposed by rays in cathode tubes, not captured with a lens or conventional camera apparatus, but it is also an experiment in transparency and gradient. Per Herbert Molderings, Moholy-Nagy began to experiment with x-ray imaging in Dessau in 1925, the same year that the hand photogram series begins.[25] Molderings writes,

As Moholy-Nagy considered X-ray apparatus too costly and complicated for amateurs, he recommended the use of processes that could produce x-ray effects without any need for special apparatus and were readily available to the photographer, such as cameraless photography.[26]

Molderings continues, “Moholy-Nagy’s light ‘compositions’ fascinate by their breathtaking remoteness from all known forms.”[27] Perhaps it is the exception that proves the rule: amidst a sea of geometric and otherwise abstract photograms emerge a series of hands (and a few faces) photogrammed to particular effect. These illuminated—irradiated—white hands against a fathomless black backdrop stand alone in Moholy-Nagy’s photogrammic oeuvre as more or less representational depictions of the human body. Along with select photograms mimicking x-rayed flowers in the amateur x-ray tradition, these hand photograms are some of the most striking products of Moholy-Nagy’s personal investment and investigation into the x-ray process.[28]

The hand photograms are an informal series based on formal affinities: Moholy-Nagy made at least 13 distinct photograms of his hands between 1925-28, though the number is likely higher and the majority were likely produced between 1925-26. One of the first hand photograms, which features the light trace of a hand’s texture as the first exposure of a print that more prominently features white coins perforating the image’s surface, may be from 1923-1925.[29] Another photogram of an exposed hand amidst strips of cut paper is dated 1923, though the catalog in which it is reproduced casts doubt onto whether this dating is correct based on its being produced during Moholy-Nagy’s time in Dessau and the formal similarity of the print to work produced between 1925-1928.[30] While the Centre Georges Pompidou dates others based on Moholy-Nagy’s period of activity at the Bauhaus in Dessau between April 1925 and January 1928,[31] one such image dated 1925-1928 by the Pompidou catalog is dated 1926 by the Museum Folkwang, Essen, which holds at least three hand photograms in its collection. I venture to guess the majority of the hand photograms date from 1925-1926 and coincide with the production of Malerie Photographie Film and its assemblage of several x-ray images. While there are several undated works from Moholy-Nagy’s Dessau period, the Centre Pompidou and its 1995 catalog suggest that two facial photograms were likely produced in 1926:[32] As written in the catalog, “Lorsque les images representant les mains ou la tete de Moholy sont dates, c’est toujours de 1925 ou 1926...”[33]

Unlike other photograms that Molderings argues are influenced by the perspectival distortions of aerial photography that promote distance and a disembodied viewer, Moholy-Nagy and his body are directly implicated in the hand photograms. In this series of photograms, there are no forms independent of the hand: they are all contingent to the hand’s presence as the thing imaged. But unlike the formally intact body found in representational photography or Man Ray’s photograms, the hand is intentionally formally penetrable. In every hand photogram, some object or form interferes with the hand’s integrity. The hands are cut by shadows, pierced by dark objects, and sometimes uncannily doubled. Some compositions feature directly layered objects while others feature multiple exposures. It is only through multiple exposures that the hands become more and more transparent: Moholy-Nagy often exposed his hand multiple times per print, repeatedly subjecting himself to a form of imaging he defined as “the penetration of the body with light.”[34] In doing so, Moholy-Nagy posits himself as both subject and object, artist and work, technician and patient. His hand serves not only as the tool of the artist-photographer but also his physical connection to the photographic apparatus itself. The hand photograms also stand alone as the only photograms that contain text: of additional consideration are at least three photograms in which Moholy-Nagy superimposes his own name over his hands (Figure 2). These photograms unambiguously identify the hand as Moholy-Nagy’s—his “signature” is, in effect, doubled.

I hope to have demonstrated that Moholy-Nagy remained preoccupied with x-ray imaging in ways that influenced his photographic theory as well as his hand photograms. This investigation reflects only the beginning of engagement with the hand photograms discussed here, as this series has been largely overlooked and not yet critically considered. Further investigations could explore the relationship of the hand photograms to the facial photograms as well as their role respective to the larger corpus of Moholy-Nagy’s photograms. Moholy-Nagy’s biography also poses questions about his relationship to his hands, as daughter Hattula recalled that his left hand and thumb were injured and deformed by shrapnel during World War I.[35] It is not only likely that Moholy-Nagy had his hand x-rayed at that time, but it is also indeed possible this experience had a lasting impact on his relationship to both his hands and his art.

[1] Linda Dalrymple Henderson, “X Rays and the Quest for Invisible Reality in the Art of Kupka, Duchamp, and the Cubists,” Art Journal 47 no. 4 (Winter, 1988): 323-340.

[2] László Moholy-Nagy, Painting Photography Film [Malerei Photographie Film], trans. Janet Seligman (London: Lund Humphries, 1969), 69.

[3] Oliver A. I. Botar, “ László Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision and the Aestheticization of Scientific Photography in Weimar Germany,” Science in Context 17 no. 4 (2004): 537.

[4] Moholy-Nagy, Painting Photography Film, 7-15.

[5] Ibid, 7.

[6] Ibid, 27.

[7] Botar also discusses this phenomenon in “László Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision”, 526.

[8] Pepper Stetler, “The New Visual Literature“: László Moholy-Nagy’s Painting, Photography, Film,” Grey Room 32 no. 32 (2008): 95.

[9] Ibid, 94.

[10] Botar, “László Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision,” 527.

[11] Ibid, 529.

[12] Ibid, 533-34.

[13] Ibid, 532.

[14] László Moholy-Nagy, “Die Photographie in der Reklame,” Photographische Korrespondenz 63 no. 9(1 September 1927): 259.

[15] Ibid, 260.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Botar, “László Moholy-Nagy’s New Vision,” 549. Huhn bleibt Huhn is perhaps anticipated by In Gottes Gehoergang (1923), a photomontage in which an x-ray of a bird is used to proffer Magnus Hirschfeld’s “Titus-Perlen,” pills for male impotence. An x-ray of a chicken extremely similar to but not the same as that used in Huhn bleibt Huhn is also used in Worship of the World Champion (1925).

[18] László Moholy-Nagy: 60 Photos, ed. Franz Roh (Berlin: Klinkhardt & Bierman, 1930): n.p.

[19] A. D. Coleman, “Introduction,” Man Ray: Photographs 1920-1934 (New York: East River Press, 1975): 5.

[20] Louis Kaplan, Moholy-Nagy: Biographical Writings (Durham & London: Duke University Press, 1995): 44.

[21] Moholy-Nagy, “Die Photographie in der Reklame,” 259.

[22] Though Schad did not dub them “schadographs,” their name represents an aesthetic epistemology that separates them from later photograms. The most obvious significance of the name besides its inclusion of Schad’s own is the double entendre of the “schadograph” as a “shadowgraph.” This inverts the etymology of “photograph” (or the more descriptive Lichtbildkunst in German), privileging the role of light’s absence instead of the light itself and suggesting that the shadows and dark areas of the image hold equal signifying weight as the light. The name could also reference shadowgraphy (schlieren photography) that made supersonic phenomena visible.

[23] Moholy-Nagy, Painting, Film, Photography, 74.

[24] Ibid, 69.

[25] Herbert Molderings, “’Revaluating the way we see things’: The photographs, photograms, and photoplastics of László Moholy-Nagy,” László Moholy-Nagy: Retrospective, ed. Ingrid Pfeiffer and Max Hollein (Munich: Prestel, 2009): 39.

[26] Ibid.

[27] Ibid, 40.

[28] Moholy-Nagy began exploring floral photograms (popular in the amateur and botanical photography circles) between 1923-1925 in Weimar before working in Dessau, where he continued to produce floral photograms into 1926 and some facial photograms in 1925-26 as well.

[29] Image 100 in László Moholy-Nagy: Compositions Lumineuses 1922-1943 (Paris: Editions du Centre Pompidou, 1995): 155.

[30] Ibid, 155.

[31] Ibid, 181.

[32] Ibid, 157.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Moholy-Nagy, Painting Photography Film, 69.

[35] “Moholy-Nagy, Perpe 1919,” Guggenheim, https://www.guggenheim.org/audio/track/moholy-nagy-perpe-1919.